Designing Lawful Military AI: Technical and Legal Reflections on Decision-Support and Autonomous Weapon Systems

This article was published alongside the PWH Report “The Future of Artificial Intelligence Governance and International Politics.”

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is no longer a speculative frontier in military affairs; it is already embedded in the day-to-day realities of armed conflict. AI-enabled technologies are increasingly integrated into intelligence gathering, surveillance, reconnaissance, targeting, logistics, and decision-support functions across militaries worldwide. Proponents argue these systems promise more accurate operations and enhanced compliance with international humanitarian law (IHL). By offering faster data processing, pattern recognition, and predictive capabilities, the claims go that AI might improve targeting efficiency, reduce human error, and limit civilian harm.

Yet these claims sit uneasily with empirical evidence coming out of recent and ongoing conflicts. Reports emerging from the war in Gaza suggest that AI-enabled decision support systems (AI-DSS) can exacerbate unlawful harm in certain circumstances rather than prevent it. For example, the use of AI-DSS to accelerate phases within the joint targeting cycle (JTC) risks encouraging over-reliance on unverified outputs. In Gaza, reporting has indicated that AI-DSS designed to generate large numbers of targets have contributed to strikes that increased civilian harm, in part due to technical accuracy limitations. Instead of reinforcing compliance with IHL, these tools risk assisting in undermining its core principles and rules around distinction, precautions in attack, and proportionality.

The central concern for us is not whether AI will likely become a permanent feature of warfare, given that it already has, but in how AI is changing the character of war, whether militaries can ensure these systems operate within reliable, accountable, and legally and ethically permissible boundaries. The stakes are high and those boundaries are difficult to draw, given that AI’s speed and scale magnify and exacerbate both benefits and harms. The truth of the matter likely is, if properly constrained, AI could potentially enhance humanitarian outcomes. If improperly integrated, AI could continue facilitating violations at a speed that outpaces oversight and meaningful redress mechanisms.

This paper advances the argument that militaries can ensure reliability, accountability, and context-appropriate human judgment and control over AI-DSS only by adopting a layered, technically sound, legally grounded framework. Such a framework requires considering and embedding legality throughout the system lifecycle and integrating AI-DSS into the JTC in a manner that not only fulfils the obligations of legal review processes, such as those under Article 36 of Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions, but also extends beyond them to incorporate broader ethical considerations.

Our analysis proceeds in three parts. Section 1 dives deeper into the gap between claims of AI-enhanced humanitarian outcomes and the realities observed in practice. Section 2 outlines a lifecycle approach to embedding accountability, structured across system design, targeting integration, and legal reviews. The piece concludes in Section 3 by briefly outlining a research agenda to address pressing questions about accountability, adaptation of legal reviews, and international harmonization.

Mind the Gap: Examining the Space Between Claims and Practice

Claims of AI-DSS increasing precision, efficiency, and IHL compliance continue to emerge. The allure of processing and analyzing data at exponentially greater speed and scale coupled with the posturing of AI-DSS as a reliable capability has resulted in miscalculated presumptions. AI-DSS are being posited as systems which may reduce civilian harm through improved targeting efficiency and reduced opportunities for human error.

On the surface these claims are reasonable, subject to the assumption AI-DSS are designed, developed, and deployed through robust systems engineering practices, which traditionally include legal obligations, such as regulatory compliance. However, this assumption has proved false. Reports on the way the Israel Defense Forces have used AI-DSS for targeting in Gaza highlight the technical inaccuracies of these systems, the absence of adherence to legal obligations, and the consequential and devastating civilian harm toll. The situation in Gaza illustrates a broader failure to adhere to fundamental obligations under IHL, rather than a straightforward breach of Article 36 review requirements. Indeed, systems such as Lavender and Gospel could, in principle, satisfy the formal criteria of Article 36 legal reviews. The challenge lies less in their design or initial assessment than in the way they are used within the JTC. Their capacity to generate vast volumes of targeting data introduces new dynamics, particularly regarding speed, scale, and operational tempo, that complicate compliance with IHL in practice. This raises unresolved questions about how legal review mechanisms can be made robust enough to address not only the legality of an AI-DSS per se but also the manner and context of its use.

Military weapon systems are categorically safety critical, where failures or malfunctions, both at a system level and an operational and process level, can result in catastrophic outcomes such as death, serious injury to people, loss or severe damage of property, and environmental harm. The nature of safety critical systems thus demands a systematically layered process across the lifecycle that is both technically robust and legally grounded. While legacy systems engineering practices prove effective for conventional weapon systems, some elements do require amendment to cater to the unique challenges of AI-enabled systems, specifically around testing and evaluation, verification and validation (TEVV) and demonstrating adherence to legal obligations under Article 36.

What we are currently seeing are AI-enabled weapon systems, such as AI-DSS, being developed and deployed outside of the systematic scaffolds of systems engineering, obfuscating required technical robustness and legal obligations. The resulting systems are thus technically inadequate and in some cases may be legally non-compliant, surfacing a misalignment between rhetoric of “responsible use” of AI-enabled weapon systems and the realities of their implementation.

If legacy systems engineering practices exist, and are applied to conventional weapon systems, it begs the question, why are they not applied to AI-enabled decision-support or autonomous weapon systems to the same extent?

In recent years the relationship between the civil technology sector and the military has grown increasingly intimate. Meta, Google, Palantir, Anthropic, and OpenAI have partnered with the U.S. military and other U.S. allies (e.g., the United Kingdom, Israel, the Netherlands, Belgium) to develop AI-enabled military systems, with both Meta and Google quietly removing long-standing commitments to not use AI technology in weapons or surveillance. Many companies within the private technology industry are characterized by the Silicon Valley ethos of “move fast and break things,” which has seemingly now to have bled into military acquisitions.18 Speed and scale are now prioritized over legal compliance and risk mitigation, practices traditionally achieved through systems engineering processes.

Robust systems engineering processes, especially TEVV, have frequently been sidelined or deliberately short-circuited in favor of rapid development and deployment, with some contending that these traditional practices are no longer fit for purpose due to the complexity of contemporary AI systems. It is true TEVV practices need to be amended to fit the specificities of AI-enabled systems; however, it does not hold true that these practices are entirely not fit for purpose.

In non-safety-critical commercial contexts, rapid prototyping and iterative development are comparatively more acceptable; by contrast, in the military domain, errors can result in loss of life or broader civilian harm. In these instances, errors are often corrected with software updates post-deployment, an approach which may prove difficult in military contexts. Nonetheless, actors in this space urge procurement processes to accelerate to accommodate speed and capability over risk mitigation and compliance. There are both technical and legal implications that come with this prioritization.

Technical Implications

Testing regimes for AI-DSS or autonomous weapons risk being inadequate to capture real-world complexity present on highly complex battlefields that differ in size, population, terrain, and transient civilian presence. It is almost impossible to curate a dataset which would completely capture every aspect of an operating environment, particularly one as dynamic and unpredictable as a military operating environment. As such, simulation environments cannot fully replicate the dynamic conditions of battle. Operations which imbricate civilian environments warrant further scrutiny, calling into question the kinds of datasets companies and military actors rely on to model these environments. Safeguards for proportionality assessments and collateral damage estimation are rarely built into system architectures, and arguably this is not technically possible. Instead, the risk is that systems are optimized for technical performance, rather than legal compliance.

Legal Implications

IHL places an unambiguous duty on states and commanders to ensure compliance. The responsibility for the obligations to comply with the law cannot be outsourced to technology. Constant care must be taken to spare civilians throughout the conduct of hostilities, and precautions must be taken in attacks with a view to avoiding, and in any event minimizing ,the incidence of civilian harm. Command responsibility persists regardless of the platform used, technology employed, or the degree of system autonomy. Military commanders remain responsible for the verification and validation of targets, and, in the case civilian harm cannot be avoided, ensuring proportionality that weighs the expected military advantage against the anticipated civilian harm.

The risk of not retaining this context-appropriate human judgment and control is not only unlawful outcomes but also reputational damage and loss of legitimacy for militaries themselves. If militaries field AI systems that cause or contribute to unlawful civilian harm, the perceived legitimacy of operations diminishes, undermining both legal obligations and strategic objectives. The current trajectory of military AI integration within the JTC prioritizes speed of development over legal compliance. A deliberate counterbalance is needed, considering and embedding legal and ethical standards structurally within the entirety of the innovation process.

A Lifecycle Approach to Lawful Military AI-DSS Systems

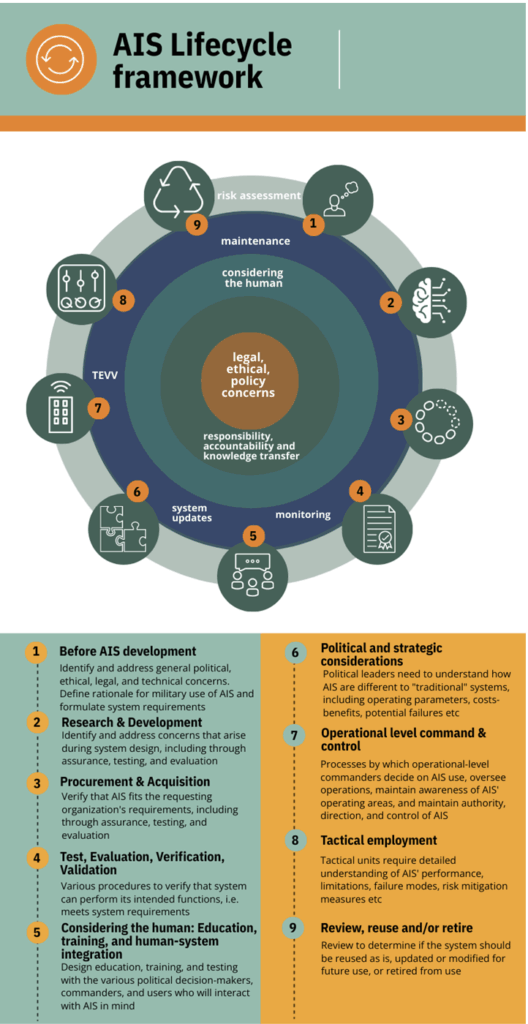

Systems engineering practices are applied against a lifecycle of a system, from inception to decommissioning. There are many variations of lifecycles across the literature. In this work, we adopt the autonomous and intelligent systems lifecycle framework developed by the IEEE SA Research Group on Issues of Autonomy and AI in Defense Systems.27

This lifecycle framework presents nine lifecycle stages and five ongoing activities which occur repeatedly throughout the lifecycle:

- Evaluation of legal, ethical, and policy concerns

- Responsibility, accountability, and knowledge transfers

- Considering the human: training, education, and human-system integration

- TEVV, monitoring, hardware system or software updates and interoperability, maintenance

- Risk assessments

TEVV is one of the five ongoing activities in this framework, highlighting the critical importance of TEVV practices across the lifecycle, including software updates post deployment.

To better reflect a systems engineering lifecycle process, we take a simplified approach to the IEEE AIS lifecycle framework, reducing it to four lifecycle stages, carrying forward an approach taken in previous work. It is important to note the four lifecycle stages encompass within their remit all of the stages identified in the IEEE AIS framework. The purpose of the simplification is to better compartmentalize where each of these stages sit across an engineering lifecycle and to then also be able to assess the military decision-making process within the JTC.

- Plan: The planning phase includes defining the scope and determining the objectives of a system. Implementing initiatives such as system cards may assist with capturing specific considerations relevant to AI and autonomous weapon systems.

- Design: The design phase involves outlining specific requirements, architectures, functions, interfaces, etc., of the system.

- Develop: The development stage involves the actual building of the system, which includes test and evaluation and verification and validation.

- Deploy: The deployment stage involves integrating the system into operations, which includes maintenance throughout the life of the system.

Lifecycle Integration

Similar to the IEEE AIS framework, lawful military AI and autonomous weapons systems are achieved through ongoing efforts or activities across the system lifecycle. Where the IEEE AIS framework presents five ongoing activities, this work differs slightly in what those activities encompass.

The IEEE AIS framework is focused on human decision making across the lifecycle, while the work set out in this paper is focused on a method towards lawful military AI and autonomous weapon systems, achieved through embedding relevant laws throughout the system lifecycle, which are complemented with technical robustness, and by integrating AI into the JTC such that Article 36 obligations are met. This proposed method will result in systems which are lawful and, thereby, are also reliable, accountable, and support appropriate human judgment. This is crucial for ensuring legal compliance. Examples of these processes across the lifecycle include:

Plan: Legal obligations must be identified early on to ensure the implications of meeting these obligations are captured in the earliest stages of the system lifecycle.

Design: Requirements for explainability and auditability should be integrated from the outset. Black-box models that cannot be interrogated for their reasoning processes are ill-suited for military decision-making.

Develop: Fit-for-purpose TEVV processes should be established and implemented to ensure these systems are technically robust and compliant with relevant laws, including technical regulations.

Deploy: Operators must receive training in both technical operation and legal accountability.

Targeting Cycle Integration

In addition to these lifecycle processes, lawful military AI-DSS and autonomous weapons are also achieved through integrating AI-DSS into the JTC such that Article 36 obligations are met. AI must be integrated into the JTC intentionally and responsibly. Transparency, auditability, and human control are essential at each stage for accountability, among other purposes: target development, validation, engagement, and post-strike assessment. Human command responsibility must remain central, meaning that AI-DSS can support decision-making but cannot replace human judgment. Particularly in time-condensed contexts, safeguards must ensure that humans retain authority to override or question AI-DSS recommendations, suggestions, and nominations.

Legal Reviews

Article 36 of Additional Protocol I (AP I) obliges states to review new weapons, means, or methods of warfare for compliance with IHL While some states are not party to AP I, and this article will not go into depth on the scholarly debate around this issue as that has been done elsewhere, but we take the position that this obligation arguably reflects customary IHL, binding even on non-states parties to AP I.

For AI-enabled systems, Article 36 weapons reviews present distinctive challenges, three of which merit particular attention for further research: dual-use software and evolving systems. First, civilian technologies adapted for military applications can blur the scope of review, making it more difficult to assess compliance accurately. This can happen in cases when civilian purposes or intentions for use differ widely from the expected military use. Second, machine learning models are inherently dynamic, meaning they can change and adapt after deployment, indicating that a single, pre-deployment review no longer suffices. Instead, continuous or iterative review processes may be required to capture these changes and any associated legal implications.

This is closely linked to the third problem of functional shifts in how a system is used. A notable example is Project Maven (now Maven Smart Systems), which initially operated as a video-analysis tool but, through operator experimentation, was later repurposed for targeting functions. Such “intention creep” raises significant legal concerns: a system originally reviewed and approved for one use may fall outside that assessment once its function evolves, triggering the need for a fresh review.

Summary and Setting Out a Research Agenda

AI-enabled systems promise greater precision and accuracy but risk accelerating unlawful harm when integrated without guardrails. The responsibility lies with militaries to ensure reliability, accountability, and context-appropriate human control and judgment. A layered framework, one developed from a multistakeholder approach, which captures the different perspectives of these stakeholders and which integrates legality and ethical compliance across the lifecycle, targeting cycle, and legal reviews of AI-enabled systems, offers the best path forward.

At least three pressing research areas emerge from our legal and technical perspectives, which we intend to continue interrogating from legal and technological perspectives but also incorporating international relations, political science, military ethics, and other relevant stakeholders as we progress:

1) Adapting Legal Reviews:

How can legal reviews account for iterative software and evolving systems? Beyond weapons-focused frameworks, legal reviews encompass “means and methods” of warfare, treating AI as dynamic rather than static. This needs to be reflected in states’ approaches to these processes, and the states themselves need to regain their position in the driver’s seat, demanding demonstrated compliance from technology companies and systems providers prior to and as a condition of procurement.

2) Preserving Human Accountability:

What mechanisms best ensure human accountability in AI-augmented targeting? This requires mapping decision points in the targeting cycle and clarifying the role of commanders relative to AI outputs.

3) International Harmonization:

How can states harmonize ethical and legal standards in the area of rapid innovation, which has historically surpassed the pace of legal and regulatory intervention? Narratives framing law as an obstacle must be challenged. Innovation and regulation are not antagonistic but mutually reinforcing when grounded in technical and legal expertise. This requires a re-narration of the innovation versus regulation framework.

Conclusion

Ensuring accountability in military AI, especially at the “sharp end of the stick” when using force within the JTC, requires considering and embedding ethics and legality where technically possible, not just thinking about or retrofitting these requirements after the system is already built or procured. Where technical limitations preclude certain aspirations, states and military actors must be clear-eyed in recognizing these limits and rejecting systems that cannot support lawful use for intended purpose. Industry narratives of “responsible AI” must be interrogated with technical and legal scrutiny and must reflect a responsible-by-design or lawful-by-design approach. Only by rigorously embedding ethical and legal requirements throughout the AI lifecycle, where technically feasible, can militaries uphold IHL and preserve the legitimacy, credibility, and moral authority of their operations in an era increasingly defined by AI-enabled warfare.