The Consequences of Repatriation are Fundamentally Shaped by Refugees’ Economic and Social Endowments

By the end of 2023, more than 43 million people were forcibly displaced across inter- national borders (UNHCR, 2023). Many of these refugees flee long-run, multidimensional political and socioeconomic crises, and face acute risks from war, repression, food insecu- rity, and climate change. Displacement is also increasingly protracted—the average refugee spends ten to 26 years displaced abroad. Given this dire situation, achieving durable solutions for displacedpopulations is one of the world’s foremost development and security challenges. Making progress on conflict resolution, development, and minority empowerment requires programmatic solutions to refugee crises.

To address the needs of the world’s displaced, the international community defines three “durable solutions”: (1) resettlement in developed, Global North countries; (2) naturalization and permanent integration in Global South countries of asylum; or (3) repatriation to origin countries when safe and dignified return becomes possible. Facilitating access to these durable solutions for refugees is critical for international security, economic development, and upholding normative and international legal commitments on refugee protection. Unfortunately, the world’s forcibly displaced people (FDP) face a fundamental solutions deficit. Over the past 25 years, no more than sixteen percent of FDP have been able to access any durable solution (Figure 2). The collapse of the international solutions architecture is particularly apparent over the past decade; since 2013, fewer than 3.8 percent of global FDP have been resettled, naturalized, or returned home. As UNHCR Commissioner Filippo Grandi put it, “forced displacement is outpacing solutions for those on the run” (UNHCR, 2022).

Important political trends underlie the refugee solutions deficit. Resettlement to Global North countries is hampered by rampant xenophobia, discrimination, and anti-refugee backlash. Public concern about alleged cultural and economic threats posed by migrants has driven widespread, mass opposition to resettlement, while globalization has also weakened the pro-migration consensus in developed economies. Hence, despite facially liberal commitments to refugee inclusion, developed states have restricted resettlement. Since 2000, resettlement rates have never exceeded 0.7 percent of global FDP stock.

Figure 1: Access to Durable Solutions for Refugees

Note: From left to right, the panels respectively plot annual shares of the world’s forcibly displaced people (FDP; i.e., refugees and asylum-seekers) who were resettled to a safe third country, permanently naturalized into a host country, or repatriated to an origin country. Data come from the UNHCR’s Refugee Population Statistics Database.

Naturalization in Global South host countries is similarly rare. Fewer than two percent of global FDP have been permanently integrated in developing countries of asylum in the post-2000 period. Both weak state capacity and low political willingness constrain opportunities for naturalization. The first barrier is institutional—75 percent of FDP reside in low- and middle-income countries with under-developed and under-resourced structures for migration management. The bureaucratic and administrative burden of refugee naturalization is significant, and though Global North countries often promise to underwrite costs, these commitments are rarely fulfilled. Political support for naturalization is also tenuous. While many Global South states have implemented liberal displacement policies intended to encourage local integration and refugee-self-reliance, citizenship remains politically contentious (Blair, Grossman and Weinstein, 2022a,b). Naturalization campaigns often succumb to political and electoral pressure from policymakers and publics concerned about identity and other sociotropic con- siderations.

Given these challenges, refugee repatriation is generally regarded as the preferred solution for refugees.Policymakers tend to favor return because, unlike resettlement or naturalization, it places no legal or fiscal responsibilities on third or refugee-hosting countries. Refugees tend to favor return because it allows them to realize fundamental rights related to citizenship and belonging (Bradley, 2013; Long, 2013). As with the other durable solutions, however, refugee repatriation has declined over time. This trend is a direct consequence of the growing duration of wars and sociopolitical crises. Since 2001, civil conflicts, which produce a majority of the world’s refugees, have become longer and more complex, involving multiple belligerent parties and frequent foreign intervention.Insecurity is the chief deterrent of voluntary repatriation, so naturally, protracted conflicts are a key barrier to return.Indeed, standard models of returnee decision-making treat war-related violence and destruction as the foremost impediment to repatriation. Conventional wisdom, then, suggests refugee return is most likely when conditions improve at origin. This view informs critical international repatriation policies predicated on the notion that FDP should return home when the underlying causes of their displacement are alleviated, such as when wars end.

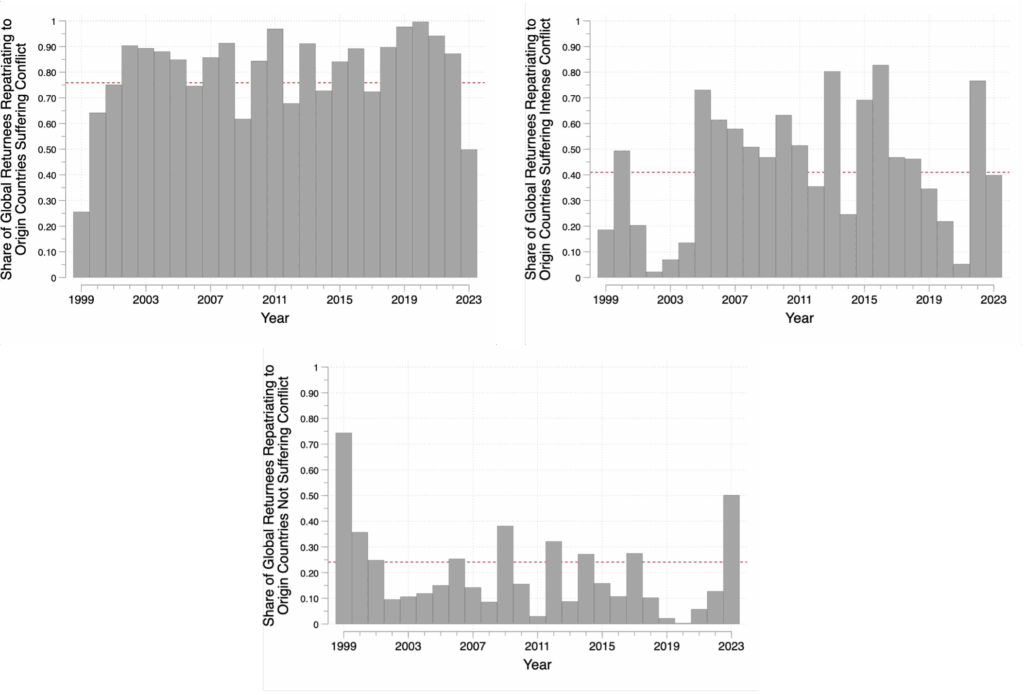

In the ideal-typical scenario, displaced people return home when conflicts end in their origin countries, making safe and dignified repatriation feasible. Yet, global repatriation patterns belie the assumption that return is only likely to occur when security improves in refugees’ origin states. For instance, nearly 325,000 refugees returned to Ukraine in 2023, notwithstanding active hostilities. Over the past three decades, 76 percent of all returnees have repatriated to countries suffering ongoing hostilities, and nearly 41 percent of repatriates returned to countries where organized political violence caused at least 1000 battle-related deaths in the same year.

Why would refugees ever return to fragile, conflict-affected origin communities? Some may choose to return, inspite of conflict risks, because they hold strong, place-based attachments to home, or because they want to affect positive change and contribute to peacebuilding in their origin communities. Occasionally, host states and international organizations directly incentivize return to conflict-affected origins through cash inducements intended to lower mobility costs and improve returnees’ reintegration prospects (Blair and Wright, 2024). Increasingly, however, refugees return to origin countries—despite ongoing violence and absent aid-based incentives to repatriate—because of worsening conditions in host countries. In particular, refugees may repatriate because of anti-migrant repression, policy restriction, or economic crises in asylum countries. If hosting conditions become sufficiently severe, the costs and risks of remaining in exile may exceed the costs and risks of return, even to conflict-affected origins.

Figure 2: Refugee Repatriation to Conflict-Affected Versus Conflict-Free Origins

Note: The top left panel plots the annual share of global refugee returnees repatriating to an origin country suffering conflict causing at least 25 annual battle-related deaths. The top right panel plots the annual share of global refugee returnees repatriating to an origin country suffering conflict causing at least 1000 annual battle-related deaths. The bottom panel plots the annual share of global refugee returnees repatriating to a conflict-free origin country. Dashed red lines in each plot mark the average share across years.

To summarize, while individuals’ return decisions are complex and idiosyncratic, there are three major conditions under which large-scale repatriation occurs: (1) improving conditions at origin; (2) exogenous shifts in mobility costs; and (3) worsening conditions in host countries. In the first, conventional case, mass return is possible because improving condi tions in origin countries, like economic booms or the end of wars, raise the relative benefits of return.In the second case, mass return is possible because programmatic interventions reduce its costliness, for instance by subsidizing transportation back to origin communities, making repatriation more affordable. In the third case, repatriation occurs, despite substantial risks of return, because of escalating costs associated with remaining in a host country. Each of these return drivers has a unique effect on returnees’ socioeconomic endowments. Different consequences of repatriation result from these distinctive contexts.

In particular, the conditions inducing repatriation bear key implications for the effects of return on conflict in refugees’ origin communities. The main way the return context matters is by shaping repatriates’ access to importanteconomic and social resources. At the moment of return, these endowments play a crucial role in facilitating or hampering returnee reintegration. Refugees returning to improving home conditions or with economic assistance are generally better-off. For one, returnees repatriating to capitalize on favorable political and economic conditions at origin, or because of direct cash support, are more likely to return with productive assets, including skills acquired and wages earned in asylum countries. Returnees induced by cash and aid programs can bolster local economies in origin communities, dampening militancy by raising opportunity costs of violent mobilization (Blair and Wright, 2024). Socially, refugees returning to fragile origin communities because of improving conditions may contribute to social cohesion, institution-building, and feelings of hopefulness. All of this suggests anti-government violence is likely todecline in communities exposed to repatriation induced by improving conditions or cash-for-return interventions.

In contrast, consider the situation of returns prompted by worsening conditions, like eco- nomic crises,sociopolitical instability, or anti-migrant xenophobia and repression, in refugee- hosting countries. Individuals repatriating under these circumstances are likely to face severe financial constraints resulting from job losses and restrictions on employment. Rent hikes, price-gouging, and police extortion may all compound refugees’ economic situations in restrictive asylum countries. Socially, negative hosting conditions are likely to depress refugees’ mentaland physical well-being, social capital, skill acquisition, and educational attainment. The combined effect of theseconditions is to render displaced people traumatized, socially-isolated, risk-tolerant, and predisposed to violence. Upon repatriating to fragile origin communities, then, returnees fleeing worsening host conditions face multiple challenges. Destitution and risk-tolerance may render these individuals ripe targets for insurgent recruitment. Similarly, social exclusion could hamper returnees’ reintegration, raising communal frictions between returnees and their non-migrant neighbors, particularly if the former lack access to informal institutional safety-nets and local dispute resolution mechanisms.

Evidence from two repatriation shocks in Afghanistan in 2016 and 2018 offer support for these arguments. In 2016, Pakistan and the UNHCR initiated a large-scale cash grant scheme, doubling the cash grant available for Afghan refugees repatriating from Pakistan. Nearly 400,000 Afghans took up this opportunity and returned. In communities to which these encashed refugees repatriated, insurgent conflict declined, mainly because positive externalities of the cash assistance raised reservation wages and blunted insurgent recruitment of otherwise vulnerable returnee populations (Blair and Wright, 2024). Social capital and informal dispute resolution institutions also helped offset the risks ofrefugee return for communal violence. In 2018, the Trump administration’s Maximum Pressure sanctions on Iran sparked a comparably sized return shock. More than 600,000 Afghan refugees in Iran returned to Afghanistan aftersanctions decimated the Iranian economy. In this case, mass return intensified insurgent violence (Blair, Krick and Wright, 2024). One reason conflict increased in 2018 was economic—destitute and marginalized returnees strained labor markets in repatriation communities, facilitating Taliban recruitment. Another reason was that Iran retaliated against U.S. sanctions by increasing covert support for the Taliban in areas returnees repatriated.

These parallel cases underscore the importance of context for understanding how mass repatriation affects conflict and stability in returnee-receiving communities. Interventions designed to bolster the livelihoods of displaced people and their non-migrant neighbors are critical. Infrastructural and economic development and local institutions for dispute resolution are key antecedents for safe and dignified refugee repatriation. Ethical and legal considerations around repatriation are also nuanced and complex. If repatriation assistance is employed to appease asylum countries eager to reduce their refugee-hosting burdens, it risks inadvertently incentivizing coercive tactics and degrading the voluntariness of return. Eroding the voluntariness of return and the free choice of refugees risks breaching fundamental principles of international law, including non-refoulement. Repatriation must occur under safe conditions when refugees themselves opt to return. Crafting sound policies requires considering the human rights issues at stake, how combatants may benefit from the return of vulnerable populations, the quality of institutions to manage localtensions, and the ethical obligations of host countries and international organizations.

References

Blair, Christopher W. and Austin L. Wright. 2024. “Refugee Return and Conflict: Evidence from a Natural Experiment.” Princeton University.

Blair, Christopher W., Benjamin C. Krick and Austin L. Wright. 2024. “Refugee Repatriation and Conflict: Evidence from the Maximum Pressure Sanctions.” Princeton University.

Blair, Christopher W., Guy Grossman and Jeremy M. Weinstein. 2022a. “Forced Displace- ment and Asylum Policy inthe Developing World.” International Organization 76(2):337– 378.

Blair, Christopher W., Guy Grossman and Jeremy M. Weinstein. 2022b. “Liberal Displace- ment Policies Attract Forced Migrants in the Global South.” American Political Science Review 116(1):351–358.

Bradley, Megan. 2013. Refugee Repatriation: Justice, Responsibility, and Redress. Cambridge University Press.

Long, Katy. 2013. The Point of No Return: Refugees, Rights, and Repatriation. Oxford University Press.

UNHCR. 2022. “High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi’s message on World Refugee Day, 20 June 2022.” United Nations .UNHCR. 2023. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2023. United Natio