Access to Asylum in the Post-Pandemic Era: Lessons from COVID-19

Executive Summary

The COVID19 pandemic profoundly disrupted global asylum systems, challenging the foundational norms of refugee protection. In response to public health concerns, states imposed a broad array of restrictions—not only at borders but also within the administrative and legal infrastructures essential for asylum seekers to access protection. This brief draws on a novel dataset, the COVID19 Asylum Restrictiveness Index (CARI), that we developed drawing on unique and unpublished cross-national data provided by the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) that captures a range policies that shape asylum access and combines them into a single index. CARI is, to our knowledge, the most comprehensive measure of asylum access during COVID19 to date and provides systematic cross-national longitudinal measures of state asylum policy during this moment of global crisis.

In this brief, we outline three key findings drawing on patterns in this dataset. First, even as states began to reopen their borders, core components of asylum systems remained restricted, revealing a disconnect between border access and access to protection. Second, countries party to the 1951 Refugee Convention generally adopted fewer and less persistent restrictions, underlining the institutional strength of international legal commitments. Third, asylum seekers’ trajectories matter: policies in transit countries significantly shaped outcomes, especially as destination states maintained long-term restrictions.

Together, these insights call for more holistic and resilient asylum policies—ones that go beyond territorial access and engage with multi-country dynamics along displacement routes. As policymakers consider future crises, this evidence underscores the need to strengthen the rights-based foundation of the international protection regime. It also invites reflection on how global systems can prepare for future disruptions while ensuring the dignity and protection of forcibly displaced people.

Introduction: Crisis, Rights, and the Global Protection Regime

The COVID19 pandemic marked a profound shock to global mobility, with repercussions for the rights of displaced populations. While border closures captured headlines, the broader effects on asylum seekers’ access to legal protection, services, and documentation were less visible but equally consequential. In March 2020, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reminded states that the pandemic did not exempt them from their international obligations to provide access to asylum. Yet, in practice, policies diverged significantly.

To monitor these evolving restrictions, UNHCR launched the Global Protection Platform, which documented how countries altered asylum systems in response to the pandemic. UNHCR regularly surveyed in-country staff specialized in asylum in all their country offices on how the pandemic was affecting asylum-seeking. Building on this data collection effort, we developed the COVID19 Asylum Restrictiveness Index (CARI). For every month where data is available, CARI provides a country-month score ranging from (no restrictions) to 100 (most restrictive). The higher a country scores on CARI at a given moment in time, the more restrictive it was for asylum-seekers to access protection.

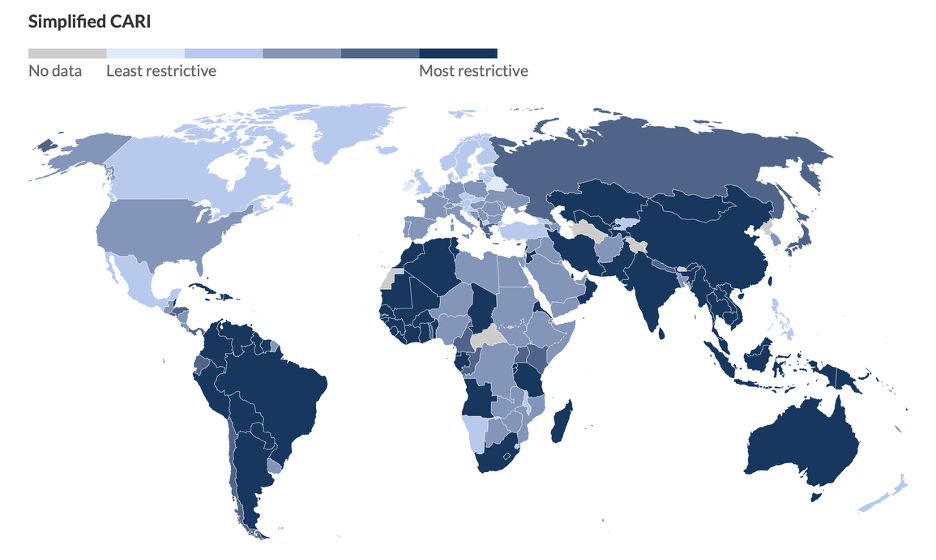

Figure 1: Global Variation in COVID Asylum Restrictiveness, May 2020

This brief distills key trends from CARI data and explores what they reveal about the resilience and vulnerabilities of asylum systems under crisis conditions. Beyond measuring formal policy changes to who was allowed into the country, CARI also captures restrictions to critical services and processes such as access to legal documentation, refugee status determination, and adequate reception facilities. These components are integral to asylum seekers’ ability to remain legally and safely within host countries. Thus, our data allow for a more comprehensive picture of how asylum protection was altered—not just whether a border was open.

Access to asylum cannot be equated with border reopening

In the immediate aftermath of the pandemic declaration in March 2020, countries worldwide closed their borders and halted travel. These restrictions, though framed as temporary public health measures, often extended to asylum seekers despite international law prohibiting states from returning individuals to places where their life or liberty would be at risk—a principle known as non-refoulement. Many actors, including UNHCR, warned that non-refoulement was applicable even in times of crisis like a pandemic, and closing borders to asylum-seekers likely constituted a violation of international law.

As states sought to balance public health concerns with international obligations, many suspended asylum processing or introduced additional procedural requirements, such as quarantine or testing rules that were difficult for displaced people to fulfill. As a result, asylum seekers frequently faced delays or denials in filing claims and receiving decisions.

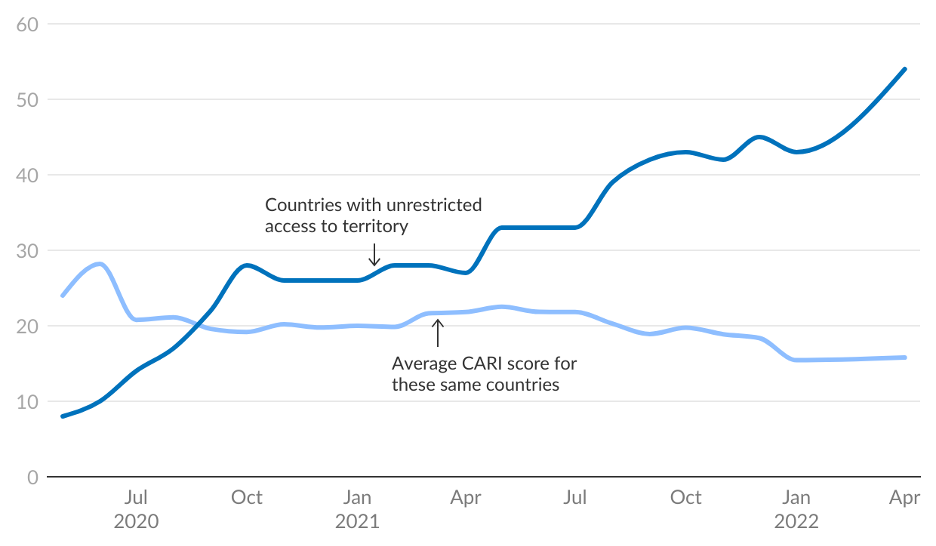

While borders began to reopen in 2021, our data show that asylum restrictiveness remained largely unchanged. As we see below in Figure 2, as more and more countries loosened restrictions related to the border (‘Access to Territory”), their overall asylum restrictiveness as measured by the CARI index remained, on average, fairly consistent.

Figure 2: Countries with unrestricted access to territory, and their average CARI score

Procedural barriers such as the suspension of asylum processing, closure of reception facilities, and delays in issuing documentation persisted. This decoupling of border access and asylum access reveals how states selectively reinstated parts of their mobility regimes, often to the detriment of asylum seekers.

These findings suggest that physical access to territory is not a sufficient indicator of access to protection. For asylum systems to function, legal and bureaucratic infrastructures must be maintained and restored alongside border management. The long-term maintenance of restrictive procedures—often beyond the acute phases of the pandemic—suggests that emergency responses risk becoming embedded features of asylum governance.

Core Refugee Institutions Matter

The 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol articulate the rights of refugees and the obligations of states, most strongly anchored by the principle of non-refoulement. While all states must uphold the principle of non-refoulement, as a bedrock of asylum norms globally, states party to the 1951 Refugee Convention or its Protocol have a duty to uphold a greater standard of treatment for refugees and asylum-seekers as well. Our analysis finds that states party to the Convention generally implemented fewer and less durable restrictions on asylum during the pandemic.

Figure 3: Comparison of CARI scores for signatory and non-signatory states

This difference is notable, especially given early concerns that the pandemic would erode the strength of the international refugee regime. The relative restraint shown on average by Convention states underscores the enduring normative and institutional influence of international legal commitments. While not determinative, Convention membership appears to shape both the scope and longevity of emergency measures affecting asylum seekers.

This finding challenges some early fears that the Convention framework might become irrelevant in the face of overlapping crises. Instead, Convention commitments—while not a shield against all restrictions—appear to have moderated their severity. They may have also created a baseline for accountability and civil society advocacy that helped protect access to asylum systems.

These results invite further inquiry into whether Convention states possessed greater bureaucratic capacity, faced distinct domestic pressures, or were more attuned to international scrutiny. Nonetheless, the association is a meaningful signal of the Convention’s continuing relevance and resilience.

Trajectories of Displacement and the Role of Transit States

Asylum is rarely a linear journey. Many asylum seekers transit through multiple countries on route to their intended destination. While comprehensive statistics are not available for all routes, in a longitudinal survey of over 2000 migrants in Italy and Greece conducted in 2020 – 2021—key countries of first arrival in Europe—the majority of respondents transited at least two or three countries before reaching Europe.

This complexity means that policies in transit countries play a crucial role in shaping protection outcomes. While destination countries—often wealthier, Convention-member states—maintained restrictions longer, transit and source countries generally relaxed their restrictions more quickly. As a result, many asylum seekers remained stranded in places with weaker legal protections and limited reception capacity.

This pattern was evident in both the Americas and the Mediterranean. In Central and South America, early restrictions gave way to more permissive policies, while North America retained stringent barriers. For example, while Central American states reduced their CARI scores within months of the pandemic’s onset, North American restrictions remained relatively high throughout 2020 and into 2021.

Similarly, in Africa and the Middle East, transit countries like those in North Africa reopened more quickly than European destination states, effectively shifting the burden of protection. In these contexts, asylum seekers were often forced to remain in countries with limited capacity to provide humanitarian assistance or legal protection, leading to prolonged periods of uncertainty, insecurity, and vulnerability.

These findings highlight the importance of examining displacement as a route-based process. National asylum policies do not operate in isolation; they interact with and often influence decisions made by neighboring or transit states. A whole-of-route approach is needed to address the cumulative effects of policy restrictions on asylum seekers. Policymakers should consider how regional cooperation mechanisms can be better structured to distribute responsibilities more equitably and protect asylum seekers’ rights along their entire journey.

Policy Implications and Conclusion: Rethinking Asylum in a Fragmented World

As the world emerges from the COVID19 pandemic, three key takeaways from this research should guide efforts to build more effective and rights-respecting asylum systems:

1. Asylum must be understood as more than access to territory. The data show that reopening borders did not equate to restoring access to protection. Legal, procedural, and bureaucratic infrastructures are essential components of any functioning asylum system. Future reforms should treat access to asylum as a comprehensive process—one that includes not only physical entry but also the institutional mechanisms that allow individuals to seek protection and legal status.

2. Disaggregated data can obscure complex interrelationships across policies. While global tracking efforts provide important insight into trends, country-level comparisons can flatten the asylum landscape. A country’s position within migration routes, its institutional capacity, and its role within international regimes all shape the nature of its asylum restrictions. To understand how policy changes affect asylum seekers, we must treat these factors as interconnected rather than isolated dimensions. That means looking at asylum policy not just as a set of discrete indicators, but as a complex and interdependent system.

3. Core institutions of the asylum regime still matter. At a time when international norms and multilateral institutions face profound challenges, it is striking that states party to the 1951 Refugee Convention were, on average, less restrictive. This suggests that institutional commitments can continue to shape behavior—even during crises. Rather than abandoning global refugee frameworks, we should invest in understanding how they affected states during the crisis and invest in bolstering and revitalizing them. The pandemic has reminded us that these institutions are not only symbolically important, but materially consequential.

These lessons underscore the need to strengthen both national asylum systems and international coordination. Resilience in asylum policy is not just about enduring the next crisis; it’s about reaffirming the principle that people fleeing danger have a right to seek protection—and that right must be meaningfully upheld.

Sources:

Mixed Migration Centre (2022), Profiles, drivers, journeys, protection and assistance challenges of people on the move towards Greece and Italy, ADMIGOV Deliverable 5.1, Geneva: Danish Refugee Council/Mixed Migration Centre.

Data Source: The Covid Asylum Restrictiveness Index (CARI) (2023), developed by Dr Lama Mourad (Carleton University) and Dr Stephanie Schwartz (the London School of Economics and Political Science), with Dr. Sarah Cueva-Egan (University of Southern California).

Note: An earlier version of this analysis was published on UNHCR’s website as a Data Visualization story in April 2024.