Systems Science, Planning, Management and Governance: An Integrated Approach

Introduction

Concerns about the efficiency and effectiveness of human actions, both in relation to the biophysical environment around us and to interactions between individuals and groups, have been with us since time immemorial. Initially focused on improving the exercise of political and administrative power in the writings of Plato in Greece and Confucius in China, ideas about how to make individual and group interventions more effective have evolved continuously.[i]

These concerns acquired greater importance during the Industrial Revolution, a period in which management methods began to focus on manufacturing, finance, transportation and other business activities, particularly in England. Innovative entrepreneurs took Adam Smith’s ideas on the division of labor and applied them systematically to the management of manufacturing and service enterprises.[ii] Outstanding among these were Richard Arkwright, the pioneer of the textile industry, James Watt and Matthew Bolton, who “brought to business an intelligence and ability usually associated only with modern scientifically trained managers,”[iii] Josiah Wedgwood, who built one of the most efficient pottery factories in the late 18th century and pioneered marketing strategies to sell his products,[iv] and Charles Babbage, inventor of the first programmable mechanical computer, who wrote a book on the economics of machines and manufactures in the 1830s.[v]

The application of the scientific method to management emerged in the United States in mid-19th century. Engineers, managers, accountants, and financiers became interested in improving the efficiency of factories and companies. The expansion of railroads made it necessary to rationalize and synchronize train arrival and departure times, spurring the development of precise scheduling methods. Toward the end of the 19th century Frederick Winslow Taylor, considered the father of scientific management, proposed four principles for management: employing scientific rigor and discarding empirical rules; fostering harmony and avoiding disagreements; promoting cooperation and leaving aside individualism; and developing the skills of each person to achieve maximum efficiency.[vi]

The first business school was established in 1881 at the University of Pennsylvania, signaling the beginning of formal management education. Similar initiatives were put in place during subsequent years at the University of California-Berkeley, New York University, the University of Texas and the University of North Carolina.

In the early 20th century Henry Ford applied Taylor’s ideas creating assembly lines to manufacture of automobiles with a stylistically austere design.[vii] A few years later Alfred P. Sloan reorganized General Motors and offered a different model each year to motivate buyers to keep up with the latest automobile style. Henri Fayol, a French mining engineer, published in 1916 a book describing the main functions of management—planning, organizing, leading, coordinating and controlling—and set out numerous principles to guide the work of executives.[viii] These developments in management science were noticed in the Soviet Union. Vladimir I. Lenin saw the importance of applying them to advance toward socialism, arguing that the “party of the proletariat, will not be able to acquire the knowledge to organize large-scale production […] unless we take it from the first-class specialists of capitalism.”[ix]

During the first half of the 20th century, contributions in various fields of knowledge nurtured the conceptions of what is now considered the broad field of management sciences. The foundation for what later would become an integrated systems thinking conception of planning, management and governance were laid during decades by advances in studies on individual and group human behavior,[x] social field theory,[xi] pragmatism and its influence on strategy,[xii]considerations on the responsibility of leaders and ethical values,[xiii] corporate planning and resource allocation methods,[xiv] mathematical statistics and quality control,[xv] strategic intelligence applied to businesses,[xvi] operational research and cybernetics,[xvii] soft systems methodology,[xviii] bounded rationality and judgments,[xix] and conceptions of governance and public policymaking.[xx]

Systems thinking, planning and management

In the early 1950s, several scholars from a variety of fields of knowledge came to the conclusion that “the need has been felt for a body of systematic theoretical conceptions to examine the general relations of the empirical world. This is the mission of general systems theory.” The increasing specialization of scientific activity and the need to link theory with action were two of the motivations that led a group of scientists from different disciplines to create the Society for General Systems Research.[xxi]

The main idea was to build bridges between scientists from different fields, in order to facilitate communication between them and to highlight common or similar aspects in their fields of study.[xxii] In his late 1970s review of the status of what he called the “systems research movement,” Roger Cavallo stated:

The last twenty-five years have witnessed a phenomenal growth in the recognition of the importance of research and systems sciences. In doing so, they have witnessed the vision and courage of a number of pioneers in various fields and from various backgrounds. They have guided science and knowledge acquisition along a broader path than that of fragmented specialization, which reached its zenith in the first half of this century.[xxiii]

Although this association brought together a large number of enthusiastic participants—mathematicians, physicists, biologists, sociologists, physicians, psychologists, historians, among other disciplines—during more than three decades, its success in building bridges was rather limited. A review of the more than 30 yearbooks published by the Society for General Systems Research reveals that, although the diversity of contributions to establishing connections between scientific disciplines showed great creativity, they fell short of formulating principles, methods and procedures that could be easily transferred from one field of science to another. The different disciplinary and professional perspectives, the aspirations of preeminence on the part of those associated with them, as well as the rigidities of the academic system that privileged specialization, made it very difficult for the postulates of general systems theory to gain traction and be generally accepted beyond a few isolated cases.[xxiv]

The emergence of alternative systemic approaches, some more focused than others, such as complexity, fuzzy sets, catastrophe and chaos theories, made even more complicated the attempts to build a unified set of concepts. While they increased the panoply of conceptual tools for perceiving and examining natural and social phenomena, they made even more arduous the task of integrating a great diversity of perspectives under the mantle of a general systems theory.[xxv]

However, as Cavallo pointed out, ”the focus of research in systems theory has progressively shifted toward the analysis of large-scale systems in which human judgments, perceptions, and emotions play an important role.”[xxvi]Likewise, Kenneth Boulding, one of the founders of the Society for General Systems Research, noted 35 years later that:

The increased interest in general systems in recent years seems to have been shown by business schools, an indication that perhaps general systems are highly relevant to the development of practical management skills, simply by allowing people to broaden the picture of their own complex environments. [xxvii]

It became clear that the pretension of offering a general theory of systems applicable to all fields of knowledge was too ambitious. In contrast, the systems approach found a fertile field in the study of decision making, planning and management. It influenced numerous conceptual developments that linked ideas and concepts with actions and interventions to guide the conduct of human affairs. According to Von Bertalanffy, “the practical application […] of systems theory to problems encountered in business, government or international politics demonstrates that the procedure ‘works’ and leads to both insights and predictions.”[xxviii]

An early indication of this shift of emphasis was a 1960s compilation of some sixty texts on systems science, which contained a few mentions to physics and biology, but in which the vast majority referred to social organizations, human behavior and learning processes.[xxix] Fred Emery edited two volumes of systems thinking contributions, which reinforced the relevance of systems thinking to social, political and management concerns. This approach became coherently articulated during the 1970s and spread widely through business schools and social science departments in the United States and Europe during the following years.[xxx] A review published in the early 21st century identified eight North American universities offering management programs based on systems science, as well as several working groups and commissions dedicated to the subject.[xxxi]

The formalization of systems theory provided a scaffolding for the diversity of ideas and concepts developed to investigate organizational behavior and decision-making. Between the 1960s and 1980s, the wide dissemination of systems approaches to planning, management and governance, led to their incorporation, either explicitly or implicitly, into the body of ideas, concepts, methods and practices aimed at improving the effectiveness of human action. They have since become a widely shared common sense.

Social Systems Science at the Wharton School

During the 1960s and early 1970s, I had the privilege of witnessing the efforts to create a comprehensive systems science approach to the study and practice of planning, management and governance. I first became aware of these development in my years as a student of Industrial Engineering in Peru. In early 1964 I was part of a small group of students who took an elective introductory course in operations research.[xxxii]

My interest in operational research and management sciences continued after graduating as an industrial engineer in 1965. The following year, I worked as an intern at the consulting firm Sigma (Science in General Management), which had been founded and directed by cybernetics pioneer Stafford Beer. There I met Russell Ackoff when he gave a lecture at the company during one of his visits to London. From 1967 to 1968 I studied for an MSc in Industrial Engineering at Pennsylvania State University, which deepened my knowledge of mathematical statistics and led to a thesis on a cybernetic lading model to control the operations of a machine shop.

In September 1968, I began my PhD studies at the Wharton School. With the guidance of numerous faculty and mentors in the Operations Research Department, faculty in other departments, and leading scholars and practitioners who visited the university frequently, I published several working papers and articles on systems science and its practical applications. Most of these were incorporated into my PhD dissertation on planning science and technology in developing countries.

Several years after founding the Operations Research Department at the Wharton School, Russell Ackoff considered the program as excessively focused on academic concerns and sought to broaden its horizons. He was keen to emphasize a greater interaction between management theory and practice. During my years at Wharton I witnessed his attempts to transform the PhD in Operations Research into the Social Systems Science program.[xxxiii] Ackoff brought together an exceptionally talented team of scholars and practitioners to teach, and to gather a diverse group of students from more than a dozen countries.[xxxiv] Most of us were involved in research and consulting projects conducted at Wharton’s Management and Behavioral Science Center.[xxxv]

Through collaborations with colleagues and students, Ackoff developed a set of theories, methodologies and practices based on systems science and operations research to improve planning, management and governance in private and public institutions. He insisted on maintaining scientific rigor, the need for holistic approaches, interdisciplinary work and the importance of learning by doing. He argued that, instead of facing problems, the growing complexity of situations forced us to deal with messes, which require integrated approaches because improving the performance of one part independently of the others could negatively affect the performance of the system as a whole.[xxxvi] He also stressed the importance of ethical values and aesthetic criteria in in our academic and professional work.

Fifteen years after graduating, I returned to the Wharton School as Silberberg visiting professor of social systems sciences, occupying for a year the chair Ackoff had held before retiring. By then, the ideas and practices of systems thinking had permeated practically all approaches to planning, management and governance. The existence of a program specifically devoted to the subject appeared no longer necessary. The vast majority of the professors with whom I had studied had left the program, and the remaining students were finishing their doctoral theses. It was anticipated that the program would be discontinued, as happened shortly after my stay as visiting professor.

A volume with contributions honoring Russell L. Ackoff was published after the termination of the Social Systems Sciences program.[xxxvii] Thirty articles outlined the history, development, and multifaceted influence of the program had during its fifteen years of existence.

While the systems way of thinking has permeated almost all areas of intellectual life and professional practice today, the challenges we face as we enter the 21st century require a renewal of our mindsets, the repertoire of concepts and ideas with which we apprehend and appreciate the changing reality.

Learning while doing

Fast forward 50 years after finishing my PhD in Operations Research/Social Systems Sciences at Penn. After a tumultuous political five-year period in my country, with four different presidents during what was supposed to be a regular five-year presidential term, in 2022 I began to reflect on why and how decisions were made during the brief time I was congressman and then president of the Republic. The idea was to unravel the various sources of influence that ended up shaping my political behavior, and take stock of what I learned and how to transmit it.

After obtaining my degree in the early 1970s I coordinated a large policy-oriented comparative research project on science, technology and development strategies and policies. My dissertation provided key inputs to the methodological guidelines for the work of teams in ten developing countries, six in Latin America and other four in North Africa, Southern Europe, and Asia.[xxxviii] Internet did not exist at that time and international telephone calls had to be booked through an operator hours or days in advance. To exchange experiences and disseminate results it was necessary to visit all the participating countries several times.

Personal contact with authorities and officials in these countries allowed me to appreciate different ways of conceiving and implementing development strategies and policies. Among other observations, I was able to see the beginnings of the Republic of Korea’s take-off, the difficulties faced by Egypt, the priority given by India to science, as well as the limitations of development strategies and public policies. At a later stage, during the dissemination of our research findings, I was able to appreciate the limitations, opportunities and different degrees of interest of Senegal, Kenya, Sudan, Singapore, and Indonesia, as well as other Latin American countries, in using scientific research and technological development to improve living standards.

After this international experience, in 1980 I helped to create and directed the Group of Analysis for Development (GRADE), which 45 years later continues to be one of the leading socioeconomic think tanks in Peru. Toward the end of the decade I joined the World Bank to lead the newly created Strategic Planning Division, where I helped to develop its Framework for Strategic Choices and later became a senior advisor to the International Relations and Policy Evaluation Department.[xxxix]

After a few years working at the World Bank, in 1993 I returned to Peru to direct Agenda: PERU, a program on development strategies, institutional reforms and democratic governance. My colleagues and I traveled all over the country to consult with a variety of stakeholders, and to test and disseminate our findings, which were also presented to the Board of Directors the World Bank and other international organizations. Agenda: PERU allowed me to learn about the extraordinary diversity of my country, which poses unusual challenges and creates many hidden opportunities. The consultation process and the dissemination of results allowed us to focus our findings on people’s concerns and to observe how political power and government authority were exercised in practice.[xl]

During this time and in the years that followed I was a member of many governing and advisory boards in national and international organizations, taught at several universities, and published numerous academic articles and books. I was also marginally involved in political activities, but after some frustrating encounters with government authorities, in 2016 I decided to fully immerse myself in polities, which meant helping to create a new political party. A series of unforeseen events would lead me to head the Transition and Emergency Government.

On November 17, 2020, I assumed the presidency of the Republic at one of the worst times you can imagine. We had three presidents in one week: one was impeached and, as he had no vice president, the president of Congress became head of state and government by constitutional succession. However, a broad wave of protests caused him to resign six days later. After a failed attempt to elect a new president of Congress, a reluctant majority of congressmen—many of them my staunch opponents—elected me to the post and, therefore, as president of the Republic. This led a political commentator to say I was “the only president elected by his political enemies.” Considering the catastrophic situation we were in; they expected me to fail quickly. I think I disappointed them.

At that time, the COVID19 pandemic was rampant. Peru had one of the highest case fatality rates in the world, no contracts to purchase vaccines had been finalized, our health system had collapsed and there was an acute shortage of medical oxygen and intensive care units. We experienced the worst downturn in our economy in decades and a series of widespread social protests. In addition, general elections were scheduled six months after I took office, in a highly polarized and toxic political environment.

How did we face these challenges? By adopting a style of governance and political leadership geared towards restoring confidence in the government and regaining hope in the future. Empowering political, business and social actors; promoting collaboration and teamwork; telling things as they were and not as we would have liked them to be; not promising what could not be delivered and delivering what was promised.

In less than six months, we secured almost 80 million doses of COVID19 vaccines, enough to inoculate three times the target population by the end of 2021. We overcame mistrust and organized joint initiatives between the government, the private sector and civil society to organize an efficient vaccination service, increase the supply of medical oxygen sevenfold and triple the number of intensive care units. We supported free and fair elections, our economy recovered rapidly, we broke public investment records, and managed social protests while fully respecting human rights.

Perhaps the most important thing we achieved was to show it is possible to govern democratically, honestly and efficiently, keeping always the common good in mind. We began our government with around 30 percent of citizen approval, and we ended it on July 28, 2021, with almost percent. It was a brief but intense experience, preceded by long years of observation and interaction with statesmen, politicians, policy makers, functionaries, business managers and civil society leaders.

Governance, planning and management

While in government, there was no time to reflect on the reasons behind our actions, but with two of my advisors we had the opportunity to do so afterwards, thanks to a grant from the Canadian International Development Research Centre.[xli]

We began to govern by calibrating the situations faced: were they circumstances, problems or conditions? Circumstances do not require profound study or debate, there are clearly defined guidelines, rules and procedures; this was the case of the general elections, for the Constitution and the electoral laws defined clearly the right courses of action. Securing vaccines was a problem, a complex situation that demanded teamwork, obtaining reliable information and hard negotiations with vaccine suppliers; we managed to solve that problem reasonably well. Social protests were a condition, with long-standing origins, multiple facets, conflicting interests, deep roots and complex consequences that could only be overcome gradually, in terms longer than those available to our government; we managed to contain most conflicts while respecting the right to peaceful demonstrations.

The central challenge we faced was to build trust in the transitional and emergency government, to demonstrate that effective democratic governance is possible. It was also clear to me that one of the most effective ways to generate trust is to bestow it. When we place our trust in others, we generate a sense of obligation in them, an inclination to prove to ourselves that they are worthy of receiving it. People of integrity and responsibility react positively to meet expectations, behaving in ways that justify the trust placed in them. This is what happened in most cases. But to grant trust is not to hand over a blank check, to depend blindly on the goodwill of others. It is to give the benefit of the doubt, until they prove themselves trustworthy or not.

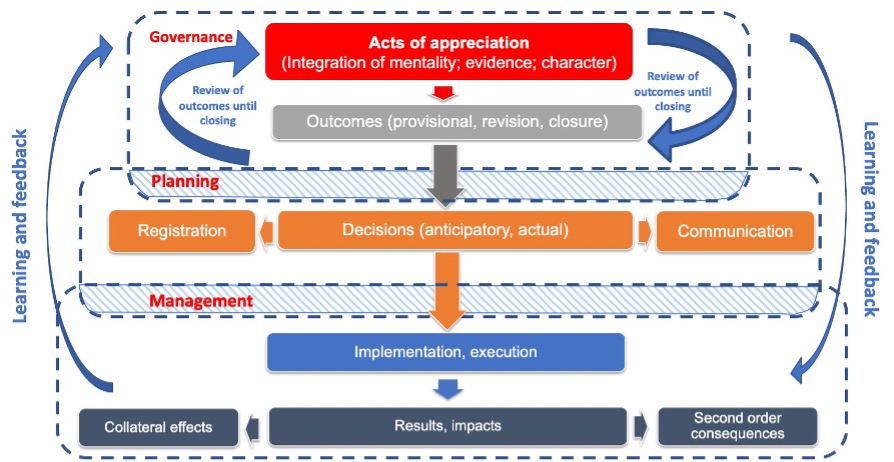

Figure 1 summarizes the way we viewed the governance, planning and management processes, their main characteristics and their interrelations. The stages they comprise overlap and their order may be altered to suit specific situations.

Governance is the central task of leaders. It consists in defining the general direction and orientation for the system to reach future situations that are preferable to the current one and provides a framework for planning and management decisions. It comprises an initial approach to the situation to determine the appropriate type of intervention, and acts of appreciation, which integrate mindsets, evidence and character through integrative judgments.

Figure 1. Governance, planning and management processes

Source: authors’ elaboration

Acts of appreciation generate outcomes that outline possible courses of action and answer questions such as: what can be done in this situation? Are there other options? Where do we want to take the system? Outcomes guide deliberate interventions, provide criteria to guide decision making, are revised as many times as necessary (and possible) to reach closure, and set the stage for planning and management.

Planning involves taking anticipatory decisions in situations that have not yet occurred but are envisaged to happen in the future. Once the general direction has been established, it is necessary to review the structure of the system under consideration, which may redefine its scope and limits, and alter the relations between its components. This may also reconfigure the system’s interactions with its task environment, made up of entities that have a direct relationship with the system, and its contextual environment consisting of entities that have indirect links to it. The idea is to make these two congruent with the orientation set up in the governance process.

The next steps are to define time horizons and the specific features of the desired states, and to elaborate a Framework for Strategic Choices that organizes the set of future options grouping them according to the nature of the decisions they involve, their similarities and differences, and the resources they require, among other criteria. Anticipatory decision become ordered set of grouped strategic lines, activities and actions arranged sequentially, identifying prerequisites and parallelisms, and deriving the demands they will impose on the system. The set of advance decisions contained in the Framework for Strategic Choices constitutes a plan that may contain more than one sets of anticipatory decisions to choose from to respond to expected and unforeseen events during the planning horizon, giving rise to different strategies.

As time goes by and the future approaches the present, management processes transform anticipatory into actual decisions. With the Framework for Strategic Choices as a reference tool, management makes the necessary adjustments to the sequence, priority and content of anticipatory strategic directions, activities and actions, and ensures the availability of resources needed to implement them. Actual decisions are recorded and communicated to track their results, impacts, side effects and second-order consequences.

Two iterative cycles of reflection complement the governance, planning and management processes. First, governance outcomes and processes are reviewed to examine the coherence and adequacy of integrative judgments. This first cycle of reflection leads to adjustments in the initial approach and in the acts of appreciation, with the idea of improving the way in which outcomes are generated in subsequent governance processes. It operates continuously during acts of appreciation, as integrative judgments are shaped and reviewed until closure is reached. The recursive review of the interactions between mindsets, evidence and character allows to accumulate experience and improve the appreciative performance of those who lead the system.

The second learning cycle requires visualizing and apprehending, in a recursive manner, all the components involved in governance, planning, and management processes. It requires a capacity for reflection, introspection and self-criticism based on sober evaluations. This cycle of reflection materialized during pauses in the work of those who govern, plan and manage the system, when it becomes possible to review and evaluate what has been done.

However, we should be aware that distinctions between governance, planning, and management are primarily conceptual. As suggested in Figure 1, governance and planning, as well as planning and management, overlap at least partially. Moreover, in practice they are often carried out at the same time in different parts of an organization, feed forward and backwards to each other, and the two iterative cycles of reflection and learning may take place simultaneously.

Concluding remarks

In their book The Prepared Leader, Erika H. James, the dean of the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, and Lynn Perry Wooten, the president of Simmons University, point out that “effective crisis leadership is about dealing with urgent and immediate needs without ever losing sight of your long-term objectives.” Scanning the environment, seeing the big picture, building resilience, mobilizing team efforts, and learning are essential to confront crisis.[xlii] In the terms of this essay, leaders should always keep in mind, at the same time, the governance, planning and management tasks that allow us to deal effectively with circumstances, problems or conditions, especially during crises.

Governing, planning and managing organizations in the uncertain, ambiguous and volatile situations that characterize our current times call for disciplined efforts to expand mindsets, gather and assess reliable evidence, and strengthen character; require the capacity to integrate these three sources of influence through integrative judgements that chart the course for anticipatory and actual decision-making. Registering and reflecting upon the results, impacts, collateral effects and consequences of these decisions allows us to reflect, learn and improve the governance, planning and management processes we are all continuously involved in our professional and personal lives.

Annex: A Closer Look at the Governance Process

The components of the governance process include the initial approach to the situation that motivates deliberate interventions, the acts of appreciation (and the streams of influence that converge to shape them) and the leadership stylesof those exercising power and authority.The initial approach refers to the disconformity that arises when confronted with a current situation of the system that is deemed unsatisfactory. It may be vague and imprecise but generates the compulsion to overcome the situation by imagining a better future situation to be achieve through deliberate intervention.

Taking into account the density, texture and complexity of causal interactions in the system and its environment, as well as the experience and knowledge of those who exercise leadership in the governance process, the initial approach to the situation being faced allows differentiating between circumstances, problems and conditions. Circumstances refer to specific situations, usually ephemeral, which do not significantly affect the characteristics and performance of the system, but which generate dissonance, disturbances and, if repeated frequently, could become problems. They usually require specific interventions for which there are rules, regulations and procedures established in advance.

Problems refer to situations whose impact on the system is greater, affect performance and its future prospects, and require broad, coordinated responses with a longer time dimension. Nevertheless, it is possible to visualize sets of decisions that configure one or more solutions to the problem in question. To solve a problem, it is necessary to adopt policies that establish criteria for identifying interventions, choosing the most appropriate ones and putting them into practice.

Conditions refer to complex situations with long antecedents, that involve the entire system, require internal coordination processes and demand a broad vision of the system’s interrelations with the environment. To deal with them adequately, it is necessary to have an idea of the objectives and intentions of the entities with which one interacts, to examine whether they are congruent and divergent with those of the system under consideration, and to respond quickly and flexibly to a series of challenges that arise incessantly from the turbulence in the environment.

In certain cases, a combination of circumstances can become a problem, and a concatenation of problems a condition. The reverse path is also possible, since conditions can be disaggregated by treating their components as problems and problems as circumstances. However, it is necessary to always keep in mind the original nature of the situations being faced.

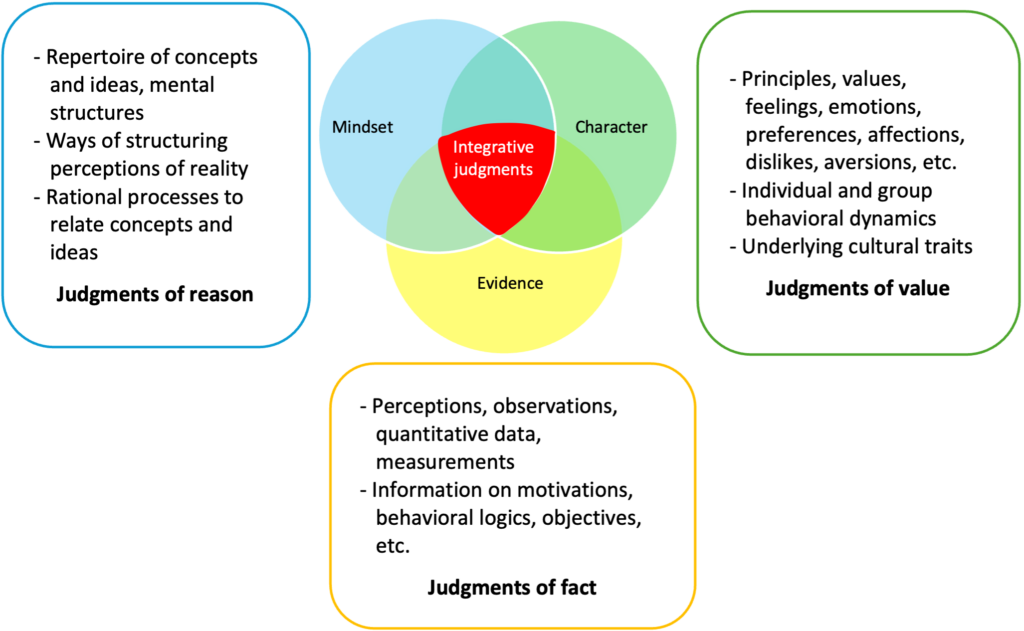

Sir Geoffrey Vickers’ notion of acts of appreciation imbricates judgements of fact with judgments of value to define courses of action.[xliii] I have added judgments of reason and leadership styles into his scheme to define an expanded version of the acts of appreciation in the governance process.

Three streams of influence are involved in every act of expanded appreciation: mindset, which includes the thought structures, the repertoire of concepts and ideas, as well as the rational procedures that link them; evidence, which comprises the data and information that provide the elements to construct perceptions of reality and are obtained through observations, measurements and inferences; and character, which encompasses the values, principles, attitudes, emotions, behaviors and also the underlying cultural patterns that give meaning to what is thought and perceived.[xliv]

The integration of the three streams of influence that shape the acts of appreciation leads to tentative outcomes, which after successive revisions arrive at a closing outcome that sets the course to be followed and guides decision-making in the planning and management processes.

These three streams of influence interact with each other and are continually evolving; it is difficult to disentangle the influence and relative weight of each, especially in situations requiring individual and group decisions at the highest governmental level in turbulent times. Changing political, social and economic situations increase or reduce the prominence and impact of certain features of the issues under consideration, giving greater or lesser importance to one or the other. They also demand frequent adjustments in the way mindsets, character and evidence combine in acts of judgment to lead to appropriate and effective decisions and outcomes (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Currents of influence in the governance process

Source: authors’ elaboration

Acts of appreciation are not carried out in a simple, sequential manner. They are continually reevaluated as they are articulated, integrating mindsets, character and evidence, employing and repeatedly adjusting integrative judgments and taking into account leadership styles. This ensures that successive outcomes progressively converge toward a closure outcome that sets the course of action for the circumstance, problem or condition being faced and leads to anticipatory and current decisions that are feasible and realistic.

Mindsets refer to the repertoire of concepts with which reality is apprehended and to the rational processes that identify, relate and order them. They can be considered as intellectual scaffolding that organizes perceptions and concatenates the reasonings that give meaning to the world around us. They comprise habits of thought that abstract essential features, identify generalities and particularities, establish causalities and recognize coincidences. They make it possible to identify options, draw conclusions, define selection criteria, guide interventions and choose courses of action that guide the evolution of the system in desired directions.

Classification and hierarchical schemes, logical and dialectical procedures and paradoxical approaches are some of the ways in which mentalities organize individual and sets of ideas. They include also the identification of the intermediate steps necessary to achieve objectives, the criteria for choosing among options that lead to them, and the ways of evaluating whether a certain sequence of decisions brings the system closer to or moves it away from the desired future situations. Mindsets guide the definition of performance indicators that feed back into governance processes and allow lessons to be drawn from experience. They are continually reconfigured through learning, incorporating new ideas and ways of reasoning over time.

Evidence comprises perceptions, observations and recording procedures that produce data, measurements, news and references of all kinds, from which descriptions and images of the real and existing, as well as of their properties and attributes, are created. They include ways of transforming these descriptions into information that allows a contrast between the existing and the desired situation, leading to interventions to reduce the discrepancy between them.

Numbers, indicators, and parameters provide inputs for statistical and mathematical methods that reveal regularities, allow inferences and conjectures, and provide ways of assessing their validity to reach conclusions on which to base decisions. They involve procedures for accessing, collecting, filtering, processing, classifying, extrapolating, presenting and using data; ways of determining the accuracy, precision and reliability of sources; and a multiplicity of ways of making them available to their users. The time lag between collection and use makes it necessary to periodically update and reinterpret data and information.

Evidence also includes recording and analyzing the motivations and behavioral logics of the different stakeholders both in the environment and within the system. This helps to anticipate the collateral effects and second-order consequences derived from the results and impacts of decisions. This category of influence includes the identification of biases, affinities and aversions of those who govern and manage the system, which affect the adequacy of their acts of appreciation.

Character comprises the principles, values, feelings and emotions that give meaning to mindsets and evidence. Modulated by affections, affinities, antipathies, passions and commitments, these components of character shape individual and group temperaments and identities. Honesty, prudence, responsibility, tolerance, empathy, solidarity and discipline are some of the values that—imbricated with attitudes such as propensity or risk aversion, preferences and rejections, optimism and pessimism, persistence and opting out, firmness and flexibility—play an important role in the examination of the options available to meet the challenges faced by the system.

The culture shared by various social groups can be considered as a substrate, generally unconscious, that conditions the evolution of character. The distinctive features of a culture affect the ways of conceiving and internalizing values—both individual and social—and can be viewed as the backdrop against which character takes shape. Self-confidence is a key component of individual character, a prerequisite to develop trust in others without which it is impossible to act with measure and aplomb when evaluating different perspectives, positions or points of view.[xlv]

Acts of appreciation integrate the three currents of influence—mindset, character, evidence—through integrative judgments to generate outcomes, which are subsequently transformed into anticipatory and actual decisions to steer the system in the desired direction. Integrative judgments are composed of reasoning, fact, and value judgments, corresponding to each of the streams of influence that shape the acts of appreciation in governance processes. The inputs coming from these streams of influence are merged, usually implicitly, according to criteria of relevance, timeliness, feasibility, reliability, efficiency, and effectiveness of the orientation that emerges as an outcome.[xlvi]

Integrative judgments determine which combination of the three streams is most appropriate, considering the characteristics of the situation being faced. When two or more sources of evidence are available, concepts and values help to decide which of them should prevail in the appraisal process; the available evidence and prevailing values delimit the set of concepts appropriate in each situation; and mindsets and evidence influence the range of values, feelings and emotions to be considered in integrative judgments.[xlvii]

A final component of acts of appreciation are the different leadership styles that refer to the ways in which individuals or groups exercise power and authority when leading to outcomes. They combine, to varying degrees, disciplinary or coercive elements (use of force, obedience, subordination, sanctions), rational elements (arguments, persuasion, reasoning, norms, institutions) and emotional elements (identification, empathy, affinity, aversion). All of these come into play, consciously or unconsciously, in the acts of appreciation that lead to outcome in governance processes (Table 1).[xlviii]

Table 1. Leadership styles

| Aspects Style | Disciplinary | Rational | Emotional |

| Basis | Authority, order, commands | Persuasion, arguments | Identification, affinity, recognition |

| Appeals to | Obedience, control | Values, principles | Feelings, emotions, affections |

| Use | Incentives, sanctions, decrees | Reasons, norms, institutions | Images, gestures, metaphors |

| Source of legitimacy | Charisma, assertiveness, use of force | Rule of law, due process | Empathy, visibility, convenience |

| Leader’s attitude | Determined, energetic, distant | Exemplary, admired, imitated | Familiar, friendly, close |

Source: author’s elaboration

Leadership styles may vary over time depending on the circumstance, problem or condition faced by the system. A prerequisite to reasonably exercise leadership by combining these different styles is learning what might be called followership. It is difficult to become an effective leader without having first some notion of what motivates those who support the exercise of power and authority.

[i] For a history of management thought from a global perspective, see: Vadim I. Marshev, History of Management Thought: Genesis and Development from Ancient Origins to the Present Day. Marshev, History of Management Thought: Genesis and Development from Ancient Origins to the Present Day (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2005), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-62337-1.

[ii] According to Adam Smith, “the maximum improvement in the productive power of labor, and the greater part of the skill, dexterity, and discernment with which it is directed or applied anywhere, seem to have been the effects of the division of labor,” quoted in Francisco Zamora, Tratado de teoría económica (Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1962), 142.

[iii] Harold B. Maynard, Industrial Engineering Handbook, 2.a ed., McGraw-Hill handbooks (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1963), 1.9-1.10.

[iv] Nathan Rosenberg and L. E. Birdzell, How the West Grew Rich: The Economic Transformation of the Industrial World (New York: Basic Books, 1986), 161-62.

[v] Philip Morrison and Emily Morrison, Charles Babbage: On the Principles xwand Development of the Calculator and other Seminal Writings, New York, Dover Publications, 1989.

[vi] Frederick W. Taylor, The Principles of Scientific Management (History of Economic Thought Books, McMaster University Archive for the History of Economic Thought, 1911), https://ideas.repec.org/b/hay/hetboo/taylor1911.html.

[vii] See: John Steele Gordon, “10 Moments that made American Business,” American Heritage (blog), March 2007, https://web.archive.org/web/20080420194514/http://americanheritage.com/articles/magazine/ah/2007/1/2007_1_23.shtml; Henry Ford and Samuel Crowther, My Life and Work (New York: Garden City Publishing Company, Inc., 1922).

[viii] Henri Fayol, General and Industrial Management (London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, Ltd., 1949), x. It should be noted that L. Urwick, who wrote the preface to the English translation of Fayol’s book, examined whether “administration” or “management” was the most appropriate translation of the French meaning of the word administration in the text. He concluded that “management” better reflected the broad range of concepts and practices proposed by Fayol.

[ix] Richard F. Widmer, “Management science in the USSR: The role of “Americanizers,”” International Studies Quarterly 24, n.o 3 (1980): 392-93.

[x] J. A. C. Brown, The Social Psychology of Industry: Human Relations in the Factory, (Middlesex, Penguin Books, 1954). Sigmund Freud’s contributions on psychoanalysis and his conception of the unconscious, as well as Carl Jung’s contributions on the theories of personality, archetypes and the collective unconscious, also contributed to incorporate the psychological aspects of human behavior into the management sciences. Years later, these developments were fully incorporated into management studies and practices by the Tavistock Institute.

[xi] Kurt Lewin, Field Theory in Social Sciences, ed. Dorwin Cartwright (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1951). See also: Eric Trist and Hugh Murray, eds, The Social Engagement of Social Science: A Tavistock Anthology, 3 vols (Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press: 1990, 1993, 1997). For a selection of early contributions in this field, see: Derek S. Pugh, David J. Hickson and C. R. Hinings, Writers on Organizations, 2.a ed., Penguin Education (Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1971). Kenwyn K. Smith and David N. Berg proposed taking into account the contradictions and inconsistencies of human behavior, arguing that it was necessary to adopt a paradoxical perspective to address the problems of planning, management and governance.

[xii] Russell Ackoff, C. West Churchman and their mentor at the University of Pennsylvania, Thomas Cowan, derived several of their ideas from the pragmatic philosophical tradition which they then employed in their early texts on operational research and the management sciences. See: C. West Churchman, Russell L. Ackoff and E. Leonard Arnoff, Introduction to Operations Research (New Yorl: John Wiley, 1967).

[xiii] Max Weber posited a distinction between ethical behavior based on conviction and ethical behavior based on responsibility, arguing that a leader must adopt a critical perspective of their own limitations, biases and affinities, exhibiting at all times a difficult combination of passion, a sense of responsibility and restraint. The Vocation Lectures: Science as a Vocation/Politics as a Vocation, (Indianapolis, Hackett Publishing, 2004).

[xiv] For much of the 20th century achieving welfare and prosperity required deliberate public interventions and policies, implemented directly by government entities or in concert with the private sector. The antecedents of state-led planning processes can be found in the work of John Maynard Keynes and Michal Kalecki in the 1930s, during which both advocated greater government intervention to overcome the crisis of the Great Depression. Various methods and instruments were developed to improve public policy decisions and to condition decisions made by private enterprises. See: Eric Jantsch (ed), Perspectives of planning, (Paris OECD, 1969), and Russell L. Ackoff, A Concept of Corporate Planning (New York: Wiley-Interscience, 1970).

[xv] E. S. Pearson, “A survey of the uses of statistical methods in the control and standardization of the quality of manufactured products,” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 96, n.o 1 (1933): 21-75, https://doi.org/10.2307/2341869. See also Acheson J. Duncan, Quality Control and Industrial Statistics (Illinois: R.D. Irwin, 1959); and Robert V. Hogg and Allen T. Hogg, “Quality Control and Industrial Statistics” (Illinois: R.D. Irwin, 1959). Hogg and Allen T. Craig, Introduction to Mathematical Statistics, 2.a ed. (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1965).

[xvi] R. V. Jones, Most Secret War: British Scientific Intelligence 1939-1945 (London: Coronet Books, 1978), 620. James Phinney Baxter, Scientists Against Time (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1968), originally published in 1946; Stephen Budiansky, Blackett’s War: The Men who Defeated the Nazi U-boats and Brought Science to the Art of Warfare (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013). See also Stevan Dedijer, Social intelligence for self-reliant development: Basis for government policy in the intelligence revolution, Department of Business Administration, University of Lund, n.o 49 (March 1985).

[xvii] Operations Research was defined as “the application of scientific methods, techniques and tools to problems involving the operation of systems, with the purpose of providing optimal solutions to the people who control the operations” in the first textbook on the subject: C. W. Churchman, R.L. Ackoff, and E. L. Arnoff, Introduction to Operations Research. Norbert Wiener laid the foundations of cybernetics, what he called “the science of control and communication” in Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, 2.a ed. (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1961, 1948), and The Human Use of Human Beings: Cybernetics and Society (New York: Avon Books, 1967, 1950). Stafford Beer explicitly applied these concepts to management, Cybernetics and Management, (New York: John Wiley, 1959) and Decision and Control: The Meaning of Operational Research and Management Cybernetics, (New York: John Wiley, 1964)

[xviii] In what he called “soft systems methodology” Peter Checkland proposed the need to consider the objectives as an open field, subject to change, to be explored and susceptible organizational learning processes. See: Peter Checkland, “Soft systems methodology,” in Rational Analysis for a Problematic World: Problem Structuring Methods for Complexity, Uncertainty and Conflict, ed. Jonathan Rosenhead (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 1989), 79.

[xix] Kenneth E. Boulding, argued that “the subjective knowledge structure or image of any individual or organization consists not only of images of ‘facts’, but also of images of ‘values'”. See: The Image: Knowledge in Life and Society (Ann Arbor, Mi.: University of Michigan Press, 1969.) For related ideas see: Herbert A. Simon, Models of Thought (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979) and his Reason in Human Affairs (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1983). Sir Geoffrey Vickers suggested a way of understanding how political decisions are made, public policies are formulated and implemented, and how government actions and interventions are managed through the integration of “judgments of fact” and “value judgments.” See: Geoffrey Vickers, The Art of Judgment: A Study of Policy Making (New York: Basic Books, 1965) and Freedom in a Rocking Boat (London: Allen Lane, 1970).

[xx] Bertram Gross used the concept of “governance” to characterize the management of all types of organizations, showing the similarity between decision-making in the public and private sectors. See his Organizations and Their Managing (New York: Free Press, 1968), and political scientist Yehezkel Dror systematized how knowledge supports the political decision-making, examining the ways in which power and authority are exercised, public policies are defined, and operational decisions are made in government administration. See: Yehezkel Dror, “The role of futures in Government,” Futures 1, n.o 1 (1969): 40-46, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-3287(69)80006-6, Yehezkel Dror, “Policy analysis for advising governors,” in Rethinking the Process of Operational Research and Systems Analysis, eds. Rolfe Tomlinson and Istvan Kiss (Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1984), 80-125, and Yehezkel Dror, The Capacity to Govern: Report to the Club of Rome (London: Routledge, 2001).

[xxi] At the meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), held in Berkley in December 1954, Kenneth Boulding, Ludwig von Bertalanffy, Anatol Rapoport and Ralph Gerard brought together some seventy people interested in the subject, which led to the creation of the Society for General Systems Research. The first of more than thirty yearbooks published by this association was published in 1956.

[xxii] Ludwig von Bertalanffy, Teoría general de los sistemas: fundamentos, desarrollo, aplicaciones (Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2007); Antonio Ruberti, ed., Systems Sciences and Modelling, Trends in Scientific Research 1 (Dordrecht; Paris: D. Reidel; Unesco, 1984).

[xxiii] Roger E. Cavallo, ed., “Systems research movement: Characteristics, accomplishments, and current developments,” General Systems Bulletin 9, n.o 3 (July 1979), 14.

[xxiv] For a review of the differences that are difficult to reconcile, see the proceedings of the North American Conference of the Society for General Systems Research, “General systems research: A science, a methodology, a technology” (Houston, Texas: University of Louisville, 1979).

[xxv] M. Mitchell Waldrop, Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992); Shūhei Aida et al., The Science and Praxis of Complexity (Tokyo: United Nations University, 1985); Heinz R. Pagels, The Dreams of Reason: The Computer and the Rise of the Sciences of Complexity (New York: Bantam Books, 1989).

[xxvi] Cavallo, “Systems research movement,” 55.

[xxvii] Kenneth E. Boulding, “Systems: Some Origins,” in General Systems – Yearbook of the International Society for the Systems Sciences, ed. William J. Reckmeyer, vol. XXXI (New York: International Society for the Systems Sciences, 1989). The name of the association changed from Society for General Systems Research to International Society for the Systems Sciences in 1988.

[xxviii] Bertalanffy, General Systems Theory, 206.

[xxix] Walter Buckley, ed., Modern Systems Research for the Behavioral Scientist: A Sourcebook (Chicago: Aldine Pub. Co., 1968).

[xxx] Fred E. Emery, ed, Systems Thinking: Selected Readings, vol. 1 (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1969); and Fred E. Emery, ed, Systems Thinking: Selected Readings, vol. 2 (New York: Penguin Books, 1981). The text that best summarizes the theory and practice of systems science in planning and management is a compilation of articles by Russell L. Ackoff, Ackoff’s Best: His Classic Writings on Management (New York: Wiley, 1999).

[xxxi] Debora Hammond, Science of Synthesis: Exploring the Social Implications of General Systems Theory (Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado, 2003), 251, http://site.ebrary.com/lib/unmsm/Doc?id=10069588&ppg=272.

[xxxii] Miguel Colina Marie graduated from MIT in 1959. Among other activities, he was a promoter of electronic engineering and telecommunications in Peru and actively participated in the installation of the first satellite communications earth station in Lurin in 1969.

[xxxiii] The transformation of the Operations Research program into the Social Systems Science program occurred in the early 1970s, and the program continued until the late 1980s. My doctoral dissertation on science and technology planning in developing countries, done under the supervision of Russell L. Ackoff, was one of the first to mark this process of evolution. Ackoff’s dissatisfaction with the traditional approach to operations research led him to write in 1979 an article critical of the professional discipline that he himself had helped to create: Russell L. Ackoff, “The future of operations research is past,” Journal of the Operational Research Society 30, n.o 2 (1979): 93-104. Moreover, he later wrote an article titled, “Never let Schooling Interfere with your Education”, included in Ackoff’s Best: His Classic Writings on Management, (New York, John Wiley, 1999).

[xxxiv] Staff faculty included, in addition to Russell L. Ackoff, Eric Trist, Hasan Ozbekhan, Howard Perlmutter, Thomas Saaty, Shiv Gupta, John Cozzolino, Julius Aronofsky, David Hildebrandt, Thomas Cowan, and Sydney Hess; faculty from other departments and faculties with whom we consulted regularly included Britton Harris, William Evan, Edwin Mansfield, Lawrence Klein, and Klaus Krippendorff, and we had frequent visits from leading intellectuals such as C. West Churchman, Ignacy Sachs, Fred Emery, Stafford Beer, John Friend and Bertram Gross. In addition, we benefited from contacts with former students of Ackoff and Churchman, including Ian Mitroff, Peter Davis, James Emshoff and Richard Mason, and later Thomas Gilmore, Jaime Jimenez, John Greiner, John Hall, Raul Carvajal, Elsa Vergara and Wladimir Sachs, as well as from the extraordinary diversity of students in the program, half of whom were foreigners, many from developing countries. The latter led me to propose to Ackoff to teach a course on operational research in developing countries, to which he responded by saying that the course would be taught by the twelve interested students and that the professors would be our students. This was done, four professors participated in all the sessions, and Ackoff mentioned this fact in one of the last lectures he gave before his death (see: Systems Thinking Speech by Dr. Russell Ackoff (YouTube, 2015), minute 35, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EbLh7rZ3rhU&feature=youtu.be.

[xxxv] Both Russell Ackoff and Eric Trist always insisted on the need to link theory to practice, and they made us see the importance of Donald Schon’s contributions on reflective practice. See: Donald A. Schon, The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action (New York: Basic Books, 1982); and Donald A. Schon, “Educating for reflection-in-action,” in Planning for Human Systems: Essays in Honor of Russell L. Ackoff, ed. Jean-Marc Choukroun and Roberta M. Snow (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992), 142-61.

[xxxvi] Russell L. Ackoff, “What’s wrong with “what’s wrong with”,” Interfaces 33, n.o 5 (2003): 81-82.

[xxxvii] Choukroun and Snow, Planning for Human Systems.

[xxxviii] Sagasti, Francisco, Susan Cozzens, Geoffrey Oldham, Alberto Aráoz, Carlos Contreras, Francisco Sercovich, Juana Kuramoto, Mónica Salazar, and Ca Tran Ngoc. Looking Back to Move Forward: A Forty-Year Retrospective of the STPI Project. Edited by Francisco Sagasti. Lima: Foro Nacional Internacional, 2015. http://franciscosagasti.com/site/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/STPI40-Looking-back-to-move-forward-Authors-copy-b_mod.pdf.

[xxxix] Sagasti, Francisco. “A Framework for Strategic Choices.” World Bank Strategic Planning and Review Department, December 29, 1988. https://franciscosagasti.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/A-framework-for-strategic-choices-for-the-World-Bank.pdf.

[xl] Sagasti, Francisco. “Agenda Perú.” Francisco Sagasti. Accessed February 21, 2025. https://franciscosagasti.com/agenda-peru/.

[xli] Francisco Sagasti, Lucía Málaga and Giaccomo Ugarelli, Gobernar en Tiempos de Crisis: Política e Ideas en el Gobierno de Transición y Emergencia Perú 2020-2021, Lima, Planeta Editores, 2023.

[xlii] Erika H. James and Lynn Perry Wooten, The Prepared Leader: Emerge from any Crisis More Resilient than Before, Philadelphia, Wharton School Press, 2022, p. xiv.

[xliii] See the introduction and chapter 1.3.

[xliv] To avoid confusion, instead of “extended acts of appreciation” I will use “acts of appreciation”. For a more detailed treatment with examples see: Francisco Sagasti, Lucía Málaga and Giaccomo Ugarelli, Gobernar en Tiempos de Crisis: Política e Ideas en el Gobierno de Transición y Emergencia Perú 2020-2021, Lima, Planeta Editores, 2023, and Francisco Sagasti, Incertidumbre: cinco Ensayos para Entender Nuestro Tiempo, Lima, Planeta Editores, 2024.

[xlv] A key dimension of the individual and collective character of those who make political decisions and define public policies is the ability to differentiate adequately between the public and the private, to have clear notions about what is appropriate and inappropriate, to distinguish between right and wrong, and to have a public service vocation, while letting others take credit for achievements. On a more reflective level, individual character also includes a willingness to have transformative experiences, a propensity to explore new options, and a desire to continually learn, especially about oneself.

[xlvi] Integrative judgments also incorporate aesthetic sensibilities, associated with expressions such as “this doesn’t look good,” “things don’t fit,” “it smells bad to me,” “I don’t like it,” or their opposite versions.

[xlvii] It is possible to link the three streams of influence and integrative judgments to Carl Jung’s psychological typology, where mentality corresponds to thought, character to feeling, evidence to sensation and intuition to integrative judgment. See chapter 1.3.

[xlviii] These types of leadership are derived from and partially overlap with what Max Weber called traditional authority, legal authority and charismatic authority. Max Weber, The Politician and the Scientist (Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 1967), 53.